This series is presented in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation

A quarter-century since the end of the war, the Courrier des Balkans has started series to examine Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy and politics, the social and environmental movements making their way through society, and the potential path to a brighter future. These articles will be accompanied by a two-day seminar on 2–3 December.

By Aline Cateux

At a table in the courtyard of Mostar’s Abrašević cultural center, Svjetlana [1] thinks back to the late 1990s and early 2000s when citizen initiatives were mushrooming in the Herzegovinian capital despite the city’s reputation for total deadlock caused by political rifts. “We had nothing left after the war. Not a thing. We had to clamor for everything. Anything we got in those years was because we fought for it. Today, take a look, they have all the things we didn’t and what are they doing with it ?” she sighs, alluding to the difficulty of finding an activist impulse in 2020 and her resentment towards a new generation that seems unwilling to invest in the future either locally or nationally. “Young people want it all and they want it now. Their path to success is money, not something you have to build patiently, brick by brick.”

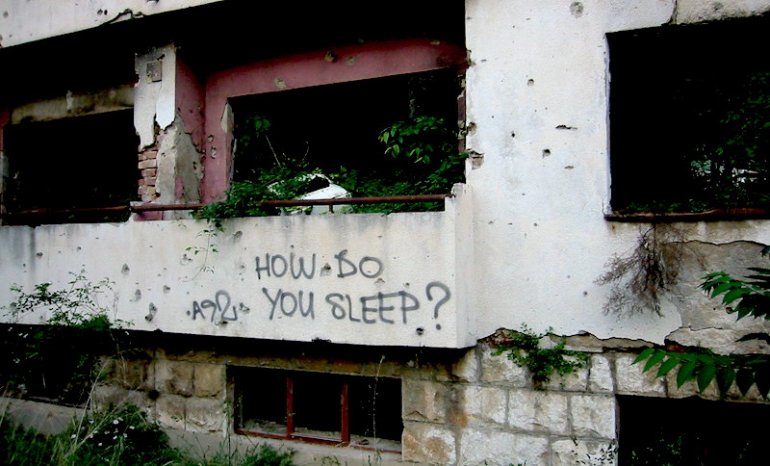

Tanja, in her forties and who was also deeply involved in the movements of the early 2000s, is more nuanced. “Our generation had it all. Then there was the war and it all went away. We had to carve out a space for ourselves amid all of that. We had to be something positive in this country that lay in ruins and accomplish things that would benefit others.” She adds, “Today, just look at what young people the age we were at the end of the war have grown up in…they know nothing but ruin and skullduggery. What kind of role model is that ?” How are you supposed to find a place for yourself ?

In Mostar, like other cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the postwar period was the start of a brief moment of activist experimentation. Public spaces were occupied and campaigns were waged to spread independent culture. The “last pioneer generation”, the last to have grown up with the Yugoslavian slogan of “brotherhood and unity”, did not seem to fit into the new postwar society, which was entirely given over to issues of ethnic allegiance. And yet they fought to make space for themselves, to exist. They campaigned for social justice and access to culture. In 2003, the youth of Mostar fought to win back the Abrašević cultural center, others faced off against Banja Luka’s city hall, controlled by the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) to open a venue for young people that would eventually become the ultrahip Geto club. Still others campaigned for conscientious objection in a country that glorified warriors.

Almost twenty years later, that generation has streamed out of the country, exhausted, disheartened, and in search of a bit of normality, a place to live and build. Those who stayed are still involved, but they are fatigued and confounded by their juniors whom they do not understand, at least not usually. “If the campaign for the Abrašević center were being held today, the collective would have no chance of winning it back. We would have no point of contact, no one would even let us in to talk. In those conditions it’s hard to keep fighting, isn’t it ?” suggests Tanja. “At the time, we had spaces we could claim, but that’s all over nowadays. Nationalism won. In 2003, we still thought we could turn things around.”

Broken transmission

Emir was born in Mostar during the war. After spending a few years on various projects, he eventually emigrated to Zagreb. The young man explains how he cannot understand the previous generation, whom he respects, but who has not passed on their experience or skills. “It’s really bizarre, they never talk about anything. There are so many things, the 2003 campaign for example, that I learned about completely by chance. They wanted us to know how to do everything perfectly and for us to be as committed as they are, but they don’t allow us the room to actually do it.” Indeed, young adults in 2020 never actually knew Yugoslavia and did not have to live through the war.

Therein lies the rub for these young people. They are twice discredited in the eyes of previous generations who deny them any legitimate right to an opinion or room to act, while simultaneously lamenting their supposed inaction and disinterest. Yet the generation born during the war and immediately afterwards grew up in a country governed by corrupt ethno-nationalist political elites. They have only seen one path to success : clientelism and guile. The impunity that reigns in Bosnia and Herzegovina disheartens its youth, who struggle to imagine a future in the country. The crackdown after the social uprisings of 2014 hastened the need to go into exile ; there is simply nowhere to express opposition, and no one seems to believe anymore that the fighting will ever come to anything.

Those who remain

Despite the emigrations and general resentment, some have decided to stay and try to build something new, to open people’s minds. “I started thinking about and researching actual facts about the war. I wanted to be educated, cultivated, and immune to manipulation,” Kristina Gadže explains. The young, 25-year-old journalist from Ljubuški also recounts the difficulty of breaking free of the nationalist discourse instilled into children. “I am aware of the trouble you can run into as a female journalist who is interested in serious topics in a patriarchal society like this one. But I’m trying to be part of the changes that are coming. Young people are the driving force of every society, even in Bosnia and Herzegovina. There are going to be some positive changes in the coming years.”

Igor Pintarić is also 25. He describes lucidly the difficulties faced by people his age who refuse to be pigeonholed by their membership of a certain ethnic group. He also talks about the social disintegration resulting from unbridled privatization and the threat hanging over the job who publicly opposes a certain party. He is disillusioned about the previous generation. “They have the strength to survive, but not to push for change. Time has worn them down, the war and the events of the past 25 years have destroyed them. All my hope lies in young people.” Igor decided to get involved to try and make a change. He is now running in the Mostar municipal elections on the citizen coalition SDP–Naša Stranka ticket. If the future remains bleak, though, he admits that he too will head West.