By Aline Cateux | Translated by Clarissa Howe

This series is presented in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation

A quarter-century since the end of the war, the Courrier des Balkans has started series to examine Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy and politics, the social and environmental movements making their way through society, and the potential path to a brighter future. These articles will be accompanied by a two-day seminar on 2–3 December.

Aline Cateux is a doctoral student of social anthropology at the Laboratory for Prospective Anthropology at the Catholic University of Louvain-la-neuve. Her work focuses on the city of Mostar, its transformation, and its pockets of resistance. She is a staff writer for the Courrier des Balkans, where she writes about Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Throughout the last three decades, a great deal of research and journalism has focused on Bosnia and Herzegovina. One cannot help but notice, however, that the same already thoroughly covered topics keep coming up : the war, ethnic relations, reconciliation, genocide, sexual violence, ethno-nationalism, and the like. Such topics overshadow 25 years of changes in a struggling society that, though seemingly mired in political and institutional stagnation (which is debatable in itself), is nonetheless vibrant and desperately searching for some kind of normality. For 25 years, the image of Bosnia and Herzegovina has been reduced to pictures of ruins – of the Mostar bridge, of women mourning their dead loved ones at Srebrenica every 11th of July, or of Sarajevo’s supposed multiculturality, as evidenced by its various religious buildings.

“Freezing” the country’s image in this way serves different interests, starting with those of the media, who remain beholden to “marketable” clichés – less out of malice than intellectual laziness. As for the academics, so often funded by Brussels, they have echoed the European Union’s (EU’s) concerns : promoting stability, reconciliation, and memory politics. A generation of political analysts has taken turns in the country to explain its impasse, often while looking aghast at the supposed “apathy” of its people. The needle finally budged in the mid-2000s when some social scientists began letting the citizens of Bosnia speak for themselves, thus giving them back their agency and explaining their survival and mobilization strategies.

The language of ethno-nationalists

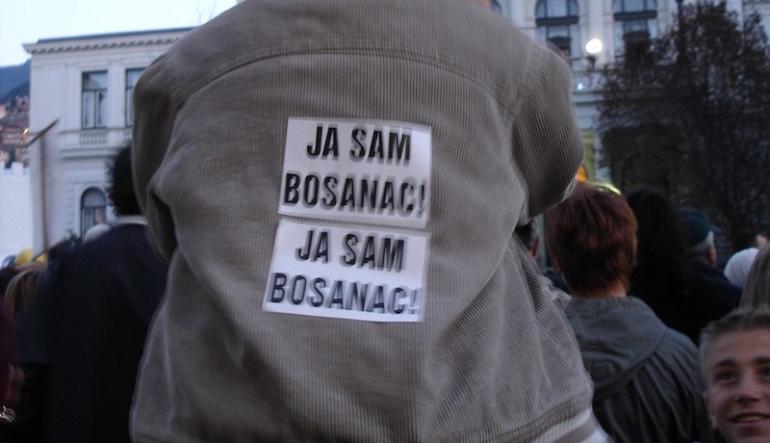

This longstanding “stereotypification” has not been without consequences, however. At some point or another, the international media, academia, and the international community have all used Bosnian ethno-nationalists’ language and reasoning, reproducing the myth of monolithic communities each with like-minded members. By smoothing over the inconsistencies, dissidences, and fluidity of social identities, they have given credence to a theoretical homogeneity, as if it were impossible to be Serb, Croatian, or Bosniak without also being Bosnian, atheist, communist, or anti-nationalist. With the ethno-nationalist vocabulary so adopted and the political elites legitimized by the international community, who partnered with those elites, what chance was there for any kind of opposition ? What space for any kind of resistance ? What legitimacy for any kind of stakeholders ?

Starting just after the war, different groups rallied behind different causes. The first to resist were the survivors of the genocide at Srebrenica, who demanded that war criminals be arrested, that the bodies crammed into mass graves be exhumed and identified, and, furthermore, that the Dayton Accords be revised, deeming Republika Srpska a “genocidal entity” devoid of legitimacy. While debates can be had today about the politicization of these survivors’ associations with their ties to the Party for Democratic Action (SDA), it does not detract from the absolute legitimacy of their demands ; these militant forces were the first to demand revisions to Dayton, a stance held today by a legion of analysts and liberal think tanks.

What of the many workers’ movements that crossed ethnic lines, including farmers defending their rights against customs duties and months – even years – of unpaid wages who went on hunger strikes in the middle of Sarajevo, veterans who survived concentration camps, and healthcare workers ? Not one year of the last 25 has gone by without strikes and mobilization. What effect has that had ? What support have they received ? These actions underline the EU’s paradoxical inconsistencies : They insist that Bosnians take responsibility for their country but look away when they exercise their rights. And threaten a crackdown when the anger boils over.

An “ethnic” reading of the 2014 plenums

The great social uprising of February 2014 is an eloquent example of how these stereotypes both act and obstruct. Many saw these social uprisings as explosions of anger that arose suddenly out of nowhere, but in fact they were nothing more than a continuation of previous movements : the demonstrations in February 2008 after the murder of young Denis Mrnjavac, which, for the first time since 1995, brought hundreds of young Bosnians onto the streets. Later on, there was the “Baby Revolution” (“Bebolucija”) in the summer of 2013, which demanded that the two entities merge ID number registries ; the movement spread to both entities. All of this led up to the labor demonstrations of February 2014.

At the time, the international media once again took the ethnic angle, pointing out that, sometimes, Bosnians were able to get past their irreconcilable enmities, come together, and burn down their institutions, symbols of a corrupt and discredited political class. Among the public, the plenums picked up where the demonstrations left off, but this was once again condescendingly regarded as the Bosnian people learning about democracy after remaining apathetic since the end of the war. After all, as a former communist country, Bosnia and Herzegovina and its citizens still need to be taught about participatory democracy, which they presumably know nothing about. Thus 45 years of self-governing socialism, factory committees, workers’ plenums, and high levels of trade union membership are ignored.

Wiping away the memory of socialism incidentally goes hand-in-hand with the memory politics the EU has imposed on former communist countries, including Bosnia-Herzegovina, which, as a former Yugoslav republic, has been cast aside. In effect, this relegates the experience of non-aligned countries to the trash heap of history. Exeunt partisans and their antifascist fighting : communism is now to be considered a villainous plot, hardly less terrible than Nazism, the 20th century’s other great totalitarianism.

What becomes of the Bosnians in this ? Corruption and impunity know no borders, not even the ones between the entities : everyone suffers. The Bosnian people are aware of their mutual interests, but the brutal failure of 2014 and the ensuing clampdown did enormous damage. For many, February 2014 was the last chance to upend the order of things, to tackle the impunity that corrupt and violent powerholders enjoy. When this call for justice failed, many Bosnians concluded that nothing else would ever be possible.

The weariness of the Bosnian people

The mass exodus affecting Bosnia and Herzegovina therefore worsened after 2014. Those who remain cling to what little they have left. They are also catching their breath. This, after all, is another aspect of the post-war period that almost never gets talked about : Bosnians are tired, traumatized, and sick. They have been thrown into a liberal transition replete with reconciliatory injunctions and they have not had time to breathe. Survivors were quickly turned into witnesses for trials in The Hague as well as subjects for journalists and academics. Little respite, zero support. No one cares about or factors in their fatigue, nor do they try to help. They have been made to rush headlong into liberal peace, swallow the bitter pill from the EU, who preaches democracy while it negotiates with corrupt politicians tied to criminal groups, and shoulder the fate of the country all while trying to put food on the table.

And yet, energy remains. Court battles are being won against environmentally destructive projects. On the local level, solidarity subsists and campaigns are being organized : an eviction avoided here, fundraising to help a child there, the illegal razing of a house prevented elsewhere. Everywhere, the Bosnian people are standing fast. One thing they have never lost is their dignity.