Interview by Aline Cateux | Translated by Clarissa Howe

This series is presented in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation

A quarter-century since the end of the war, the Courrier des Balkans has started series to examine Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy and politics, the social and environmental movements making their way through society, and the potential path to a brighter future. These articles will be accompanied by a two-day seminar on 2–3 December.

Daniela Lai is lecturer in International relations at Royal Holloway College, University of London. Her researches focus on socio-economic reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina since the end of the war and on transitional justice.

Aline Cateux (A.C.) : How would you describe « the international intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina after the Dayton Peace Agreement » ?

Daniela Lai (D. L.) : When I talk about ‘international intervention’ in my research, I refer to the set of reforms and policies put in place by various international organisations and states in the aftermath of the Bosnian War. This does not necessarily mean that international actors always worked with a unified purpose or strategy – they didn’t – but they all operated with some key general goals in mind : state-building, peace-building (with a specific kind of ‘peace’ in mind), and the transition to a market economy.

In practice, the international intervention in BiH was complex and far-reaching, and included military as well as civilian components, political and economic reforms alike. In my research, I focus specifically on two aspects of the intervention. First, I look at internationally-sponsored efforts at transitional justice and dealing with the past – which in the Bosnian context mostly meant the establishment of prosecutions for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide at various levels (from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to domestic courts). Second, I analyse the international intervention from the point of view of economic reforms aimed at completing Bosnia’s transition to a capitalism system and its integration in the global economy.

While these two dimensions of the intervention are often studied in isolation or independently from one another, I argue that it is essential to consider how they jointly affected how the Bosnian society could deal with the legacies of wartime socioeconomic violence and its chances of achieving some form of socioeconomic justice after the war. By promoting limits to public spending, privatisation and welfare reform, international financial institutions – like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank – can effectively constrain the scope of redistributive policies and social programmes that could help tackle socioeconomic injustice. In other words, these organisations play an important but dramatically understudied role in justice processes.

A.C. : Questions of dealing with the past and reconciliation have been made priorities in the peace-building process, how did this play in bosnian and herzegovinian society ?

D.L. : This is a very good question. Yes, transitional justice, peacebuilding and reconciliation were a big part of the international intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, it is important to highlight that international actors attributed specific meanings to ‘justice’, ‘peace’ and ‘reconciliation’. In other words, they had specific images of what they would look like. For instance, justice was mostly about the individual criminal responsibility of war crime perpetrators, and about establishing the ‘rule of law’ in the new BiH state. But if we look at what BiH citizens mean by ‘justice’, we get a much more holistic and nuanced picture. Alongside the kind of justice done in courtrooms, the people I interviewed for my research wanted socioeconomic justice too. During the war many Bosnian cities and communities lost their industries (which had employed thousands of citizens) ; they lost neighbourhoods that were destroyed, and they lost access to the socioeconomic life of their town.

Many of these processes started in very violent ways during the war, but then continued in the post-war period, partly as a result of the international intervention I described earlier. This situation contributed to the outbreak of mass protests in 2014, and continues to affect BiH today, 25 years after the end of the war. International approaches to post-war justice and peacebuilding did not really capture this dimension, because they saw political economy as rather unrelated to ‘justice’, which they understood in a narrow legalistic sense. However, this connection between political economy and justice was very clear to the Bosnian people who took part in my research.

Similarly, when it comes to ‘reconciliation’, which is a rather contested term, this was defined in terms of reconciliation among different ethnic groups, which contributed to reinforcing the ethnic framing of social divisions in BiH and, as other scholars have pointed out, was often pursued through elite-driven projects that did not have broad resonance in the Bosnian society. However, this is not the only possible way through which we can conceptualise the overcoming of social divisions in post-conflict contexts. For instance, the 2014 protests showed us that mobilising around socioeconomic issues can potentially build civic forms of solidarity among citizens.

A.C. : Can you describe the type of economical criminality that BiH is facing ?

D.L. : In my work I do not necessarily address ‘criminality’ as such, but rather violence and injustice. I define socioeconomic violence as a kind of violence that is rooted in the political economy of the war, which in the Bosnian case was based on the seizure of social property, material deprivation, trafficking, and the destruction or repurposing of infrastructure, including industrial infrastructure, for war-related purposes. The lack of redress for this kind of violence and some of the interventions of international financial institutions I mentioned earlier ended up entrenching socioeconomic injustice after the conflict.

These processes do not easily correspond to legal categories of criminality. I found it more fruitful to analyse this dimension of the war through the conceptions of violence and injustice because they also better captured people’s experiences of the conflict and the post-war transition. Following from this, I understand socioeconomic justice as the process through which we provide redress for socioeconomic violence, one that is centred around the notion of redistribution, and also participation in economic as well as political decision-making (following political theorist Nancy Fraser). So, if we frame your question in terms of socioeconomic injustice rather than criminality, I definitely think that BiH is still affected by the long-term consequences of what I called socioeconomic violence, in terms of deindustrialisation, the loss of labour rights and protections, the dismantling of communities through emigration, and so on.

A.C. : Did the social uprisings of 2014 changed anything in terms of socio economical justice ? If not, why ?

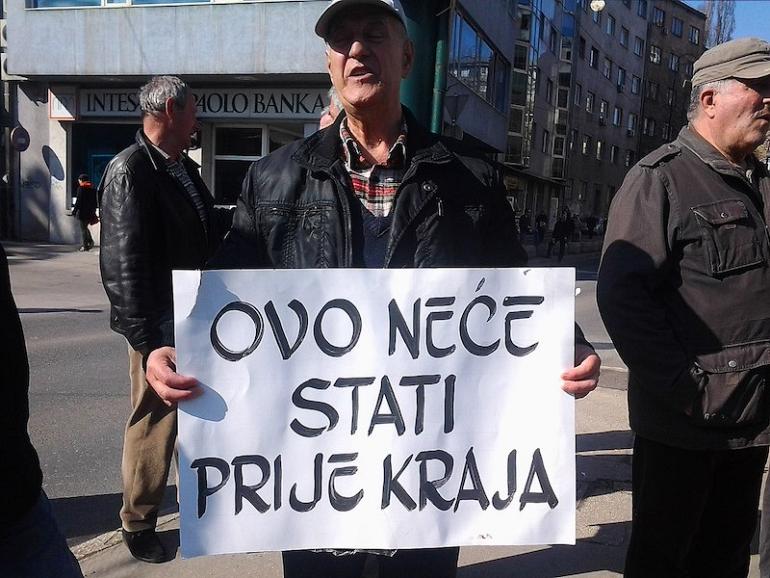

D.L. : As I mentioned earlier, we can see some of the root causes of the 2014 protests in socioeconomic processes of destruction and dispossession that started with the war. So these are problems that are really entrenched and have a long-term character, and which will require political efforts at multiple levels in order to be reversed. However, the 2014 protests were very important and influential for several reasons. They were the largest popular mobilisation to happen in BiH ever since the start of the war.

They were explicitly against the ethnonationalist rhetoric so widely used by political elites, and tried to present their claims in civic terms – as issues that interested citizens of BiH as a whole. Moreover, it was quite significant that the protests managed to bring back into the public discourse ideas of social justice that had been side-lined over the previous decades. So there may be various reasons why the protests’ impact was limited, one of these being the ethnonationalist system established through the Dayton Peace Agreement, but their importance should not be underestimated.

It should also be noted that the protests did not come out of the blue : they built on pre-existing grassroots activism, and on previous protests – such as the 2013 protests about the unique citizen ID number ((jedinstveni matični broj građana) and ‘right to the city’ protests in Banja Luka the previous year. Even though the protests may have not brought about comprehensive change, grassroots activism in BiH did not go away and will continue to push for change.

A.C. : What is the current situation regarding socio-economical justice in BiH ?

D.L. : To answer this question, I would like first to highlight some of the socioeconomic justice claims formulated by research participants I spoke to in BiH (specifically in the cities of Prijedor and Zenica). They wanted compensation for not being reinstated in their jobs after being unfairly dismissed (often on the grounds of ethnicity) during the war ; they wanted to be part of economic decision-making that affected their cities (for example, on the privatisation of the steel mill in Zenica) ; they wanted better welfare support and active employment policies conducted by the state, to compensate for the loss of being cut out from the socioeconomic life of their city as a result of the war. Unfortunately, many of these things have not materialised and do not appear forthcoming.

Political elites bear a lot of responsibility, and at the same time the international community should also recognise that some of its policies – neoliberal policies of liberalisation, privatisation, and budget cuts – may have contributed (and continue to contribute) to the lack of socioeconomic justice in BiH today. In this sense, the situation in BiH is, on the one hand, a product of the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the Bosnian War with all of its political legacies, but also, on the other hand, a reflection of a particular international approach to ‘transitions’ to peace and liberal democracy that privileges market reforms over socioeconomic justice.