Recorded by Jean-Arnault Dérens

This series is presented in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation

A quarter-century since the end of the war, the Courrier des Balkans has started series to examine Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy and politics, the social and environmental movements making their way through society, and the potential path to a brighter future. These articles will be accompanied by a two-day seminar on 2–3 December.

Muhamed Blažević is the vice-president of the Bosniak Cultural Association of Geneva.

Courrier des Balkans (CdB) : How long have you lived in Switzerland ?

Muhamed Blažević (M.B.) : I was born here in 1994. My father had come here one year earlier as a refugee and my mother had been living in Switzerland since 1989 as an au pair for my father’s older brother, who had emigrated before the war. Both my mother’s and father’s sides of the family come from Kozarac, near Prijedor.

CdB : And when was the first time you went to Bosnia and Herzegovina ?

M.B. : July 2002. It was also my parents’ first time going back after the war. They couldn’t go back while they still had refugee status. Still, I knew all about the house that was rebuilt and the village thanks to pictures, videos, and everything my parents and grandparents, who were also refugees in Switzerland, had told me. I remember an immense feeling of freedom once we passed through the little border post at Bihać, a feeling that I’d finally come home. My mother told me that for four weeks, I didn’t utter a single word of French. But once we got back to Switzerland, we started speaking French again to my brother, who is four years younger than I am. Bosnia and Herzegovina was freedom ; in the village, I could do all the things that a child in an apartment in the city cannot.

CdB : Kozarac is located in present-day Republika Srpska. Did that mean anything to you as a boy ?

M.B. : No. It wasn’t until the Arab Spring in 2011 that it started to mean anything to me. That was when I was in high school and started getting into the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I had always spent a lot of time with my grandfather, and he told me quite a lot about it. The stories from the war were very present in my life, but no one ever mentioned what the country was like after the fighting stopped. It was really during the Arab Spring that I started feeling like I had two cultures and that I’d been given two upbringings : one totally Bosniak and one totally Swiss.

CdB : What does it mean to have a Bosniak upbringing in Geneva ?

M.B. : Learning the language, the culture, certain customs. We always spoke Bosnian at home, and my son, who’s five months old, will speak Bosnian as well. It’s also a matter of spiritual and religious upbringing. The power of an identity is the ability to take what you learn at home into the outside world. I am incredibly lucky to have grown up in Geneva, an international city where cultural differences are the most normal thing in the world and where all sorts of identities mix and mingle. I am of the opinion that we all have a complex identity ; it’s never monolithic.

CdB : Your identity has a strong spiritual side, but Bosnia and Herzegovina is a country where multiple religions coexist…

M.B. : Absolutely. It’s richly diverse. I became keenly aware of that the first time I went to Banja Luka and met people my age who were Serb and Croat. We have different religions and cultures, but we can still be friends….In Bosnia and Herzegovina, we have a special kind of separation between church and state that worked very well for centuries, both under Tito and well before him. Today, though, people look for made-up tensions when recognizing our differences could bring us closer….When I was younger, we lived in a building with two Bosnian Serb families, one with a child my age that I went to high school with. It is an asset to grow up with diversity, that should be instilled in our upbringing. I can’t blame a young Serb today for what happened in Bosnia during the war.

CdB : Does it mean anything to you when people talk about Yugoslav identity ?

M.B. : No, not for my generation. Of course, I often hear people talk up the Yugoslav era. Before the war, my father worked in Bosnia. For him, Switzerland wasn’t at all part of his plans. Some of his brothers were already working there, but as seasonal workers in unstable conditions. As for him, he had a good job, earned better money, and lived better in Yugoslavia than in Switzerland ! A lot of people say that life was better under Tito, even young people who don’t remember that era. I find that a bit strange, because you can’t dissociate Yugoslavia from socialist ideology, but it certainly goes to show how bad people’s lives are these days.

CdB : Did you learn about the breakup of Yugoslavia in school ?

M.B. : No, never. One teacher told me it was too recent, even though we had classes about September 11 and even the Arab Spring. I think the teachers didn’t want to talk about the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina because it happened in Europe, on our continent.

CdB : Does the spiritual part of your identity go beyond the Bosniak community, or do you keep your practice of the faith within it ?

M.B. : No, not at all. In the neighborhood where I grew up, there was a Kosovo Albanian mosque. I used to go there often, and I also go to the big mosque in Geneva, which is a “multiethnic” mosque… You feel different things there. The strongest emotion I ever felt was at the Blue Mosque in Istanbul !

CdB : How does your generation get along with older ones ?

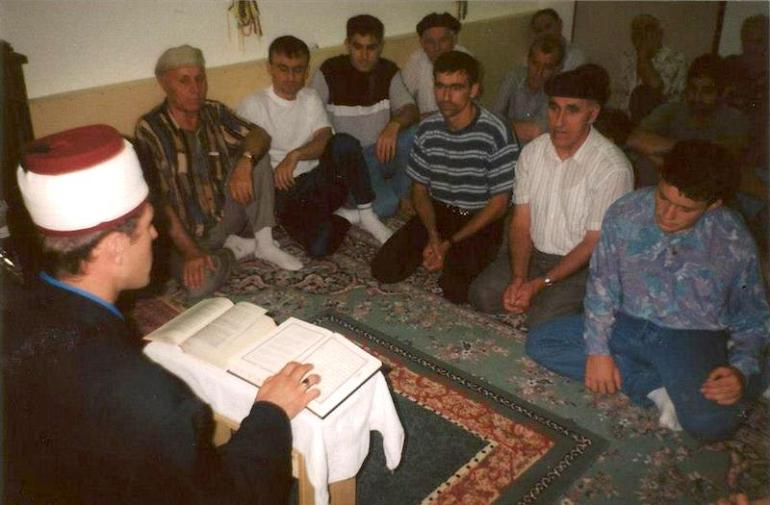

M.B. : Really well ! We learn about the history of our country from our elders. There was already an established diaspora in Switzerland before the war, but an entire generation arrived in 1993-94. They lived together, initially in collective centers, which bonded people together. Then they kept seeing each other to welcome new arrivals. Even with the modest sums refugees were given, people would save up to send money back home. Džemat, Geneva’s Bosniak association, was created in 1993 and I grew up with it. Ever since I was about eight or nine, I’ve known that I could help people because I could read and write in two languages : French and Bosnian.

CdB : Could you tell us about what Džemat does ?

M.B. : It’s mostly an association where people help one another, but it’s also a cultural and spiritual association. We hold classes on language, history, culture, and religion as well as events. We also run a little café and store that is open to everyone and a community place of worship. Our imam came here in 1997 when he was only 25 and had just finished his studies. He also had all of his “firsts” in Geneva, like his first time teaching and first time preaching. On Sundays, he teaches 120 children under twelve from 9 am to 10 pm. On Saturdays, the children have soccer – there’s a young Bosniak network with the other Džemat groups from French-speaking Switzerland, like Lausanne and Yverdon. It’s important to get together like this, it’s not communautarisme. (Note : communautarisme, “communitarianism,” used in French to refer to a phenomenon of one ethnic group not integrating with the rest of society.)

CdB : You’ve brought up quite a dangerous concept there that’s not usually well defined. What does communautarisme mean to you ?

M.B. : It means that that group is withdrawn into itself. You might say that what we do is communitarianism in a good way that is open to society. We get together because we have something in common but also to get more involved in society, both in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Switzerland. The goal is to grow and change together. Someone who is with us is not against the canton of Geneva or Switzerland, on the contrary ! We try to do things that benefit everyone, especially in the area of social justice. A lot of people who have been part of Džemat get involved with nonprofits or even go into politics. Džemat is represented in the Geneva Union of Muslim Organizations as well as on the canton’s Interreligious Platform.

CdB : Do you go to Bosnia often ?

M.B. : Usually yes, but I’m heartbroken because I haven’t been there in over a year due to coronavirus.

CdB : Do you think you might go back and live in Bosnia and Herzegovina ?

M.B. : My oldest uncle, who is 63, always used to say he would go back when he retired, but now that he has six grandchildren in Switzerland, so I dare him to spend more than three months in Bosnia ! The same goes for my father, who’s just had his first grandson. People of that generation always said they would go back one day, but they know very well that it’s not true… They’ll be back in Switzerland at the first little health scare. As for me, I was born here, I live here. I can’t live without the village, but it’s for vacation. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a beautiful country, Tito made Yugoslavia the center of the world between the West, the socialist countries, and all the non-aligned countries, but just look at what’s left. Since the war ended, they’ve tried to rebuild, but it hasn’t worked. They need to figure out why. Politicians put themselves first and stoke tensions. How can anyone live in that environment ?

CdB : So your son Ahmed is going to grow up in Geneva, but won’t he also have two cultures ?

M.B. : Of course, he’s going to grow up as a Genevan Bosniak. I will give him what my parents gave me : the language and the culture. Ahmed isn’t exactly an easy name to have, nor is mine, Mohamed. Often, when I talk to someone who doesn’t know me, they are surprised when I introduce myself because nothing about my physical appearance or accent would signal that I’m Muslim. I’m proud of what we are. My mother started wearing hijab in the 1990s, just after I was born. I grew up knowing how people would sometimes look at her – and the looks are getting harsher – but I’ve always been proud of my mother.

CdB : You work for the railways like your father. What was your career path ?

M.B. : Après le lycée, je n’avais pas envie de faire de longues études. J’ai fait l’armée puis j’ai intégré le service cantonal de la population, dans le secteur de l’asile et des migrations, mais j’ai très vite été déçu. Je pensais que j’étais là pour aider les gens, mais le règlement de Dublin est terrible. Je suis parti au bout de trois mois... Mon père, lui, quand il est arrivé en Suisse, il a été accueilli, aidé. Ensuite, j’ai travaillé durant trois ou quatre ans comme chauffeur de bus : c’était un rêve d’enfant, et c’était merveilleux de pouvoir sentir directement toute cette diversité de Genève. Maintenant, je suis chef de la circulation des trains.