This series is presented in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation

A quarter-century since the end of the war, the Courrier des Balkans has started series to examine Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy and politics, the social and environmental movements making their way through society, and the potential path to a brighter future. These articles will be accompanied by a two-day seminar on 2–3 December.

By Marko Tomaš

Marko Tomaš was born in Ljubljana in 1978. He writes poetry, columns, essays. He lives between Mostar, Zagreb, Ljubljana and Belgrade. After about ten poetry collections, he published his first novel „Nemoj me buditi“ („Don’t wake me up“) (IK LOM, Belgrade/ V.B.Z. Zagreb)

In the mid-1990s, just after the war, some of us very naïvely believed that it would all soon work out and that life would pick back up where it left off. The most naïve among us even thought we could have a “clean slate” and rebuild the best society imaginable. That fatalist component of the Slavic soul that some call melancholy had just been a mirage. Slavic melancholy, though, is nothing more than an inborn, genetic predisposition towards all kinds of illusions, but especially political ones. Despite that, in the euphoria sparked by the end of the war, very few people examined what was happening in detail. We were going to rebuild the country, money was flooding in and everyone spent it as they deemed best. Looking back, I think everybody figured that, after everything that had happened, they deserved a chance to relax for awhile.

The brief golden age of independent culture

In the latter half of the 1990s, Bosnia and Herzegovina experienced its golden age of independent culture. Official cultural institutions were not yet fully up-and-running, their offices were under construction, and the civil servants who remained were only concerned about maintaining an air of continuity. It was these unusual circumstances that gave birth to independent institutions in many cities. These institutions quite often depended on funding received from appeals to international projects. Numerous small musical groups were formed in Sarajevo, Travnik, Banja Luka, and Mostar. Meetings and festivals were held that brought together informal collectives and independent cultural associations. These encounters made it look like an independent arts scene was being created that could leave a lasting mark on the next decade. But it was not to be. As so often in Bosnia and Herzegovina, looks turned out to be deceiving. It was simply one of the many illusions borne of the postwar euphoria.

Most of the musical ensembles, literary and student magazines, and festivals started at the time have now been consigned to the past. Many of these initiatives disappeared as far back as the early 2000s. Only a tiny fraction survives on life support. Nobody at the time – not the donors, not the organization members – worried about the viability or sustainability of the projects and the bubble we were living in started to burst as soon as the international community found other interests. All that survived were a few associations involved mostly in politics and civil society. Arts and culture remained on the fringe.

The new, official cultural institutions brought to life during this time of reconstruction began falling prey to the ethno-nationalist parties by the early 2000s. This only further marginalized independent culture. The time had come to push the cultural narratives they had gone to war for. As pressure from these narratives became more intrusive, some independent cultural stakeholders felt the need to maintain some kind of continuity with what had come before. We began demanding our right to remember because we felt the ground giving way beneath our feet. They refused us our right to any cultural identity that did not conform to the parochial interests of the nationalist elites in power.

Preserving memory

And so the culture of memory has become the dominant theme for those Bosnian artists who refused to cater to nationalist mythology. Under these harmful cultural policies, Bosnia and Herzegovina began its fragmentation into three different sets of public opinion, three official truths that have nothing to connect them. That which independent culture sought to unify right after the war was quickly torn asunder by the development of aggressive, revisionist cultural projects. This free-for-all was the death knell of the common culture built over 70 years of shared Yugoslav history. Official culture – or, rather, official cultures – steamrollered the alternative arts scene, leaving it to its fate and to a nonexistent “market”. All that survived were the few artists that managed to reach a broader audience.

This fight for the culture of memory, or more specifically for cultural and therefore also social and civil continuity, is most important in cities, which bear the brunt of the effects of the war. The devastation was not restricted to the destruction of public and private buildings. Urban populations were scattered, their way of life completely turned upside down. The culture of memory, the fight for a right to remember, is therefore more than anything the fight to preserve a way of life.

My hometown of Mostar is a textbook example of the all-out assault on the private and collective memory of postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina. Mostar is also key to the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The process of integrating the city could indeed have been a model for integrating and reforming the country. It was especially important to destroy the city and completely dissolve its cultural heritage to allow political elites to serve national interests, which are never anything more than a vulgar political disguise for the personal interests of the people in power. Nationalism is itself devoid of all ideology. It is an end unto itself and endures by dint of perpetual conflict and the sheer difficulty of fighting in such circumstances for the right to one’s private memories.

What this demonstrates is the vital importance of all the cultural initiatives that seek to establish and maintain ties to Socialist Yugoslavia, the era of the greatest economic and cultural progress ever recorded in the region. The violent excision of this part of its history and collective memory condemns both Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as its neighboring countries to stumble through a mythologized, para-historical version of the Middle Ages. This is how we end up with a culture cleansed of all modernism and progressivism. The intent of such ethno-nationalist visions is to drive people as far apart from one another as possible. Ultimately, the only possible outcome is to physically dismantle Bosnia and Herzegovina. What country actually, desperately needs is a different way to relate to its common heritage, which is the only thing it can keep intact and turn into a potential model.

The example of Mostar

Mostar-born historian Dragan Markovina has published an entire series of excellent works on the culture of memory. His book Between Red and Black : Mostar and Split in the Culture of Memory is the kind of book that could be used to spark deeper reflection in order to normalize how Bosnia and Herzegovina’s ethnic groups relate to their shared heritage. Theatre critic Salko Šarić’s Mostar Arts Review is an encyclopedia of sorts that might serve the same purpose. These works reveal just how many cornerstones of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s history and culture have been neglected. They are evidence of the general decrepitude of the State and how little importance its leaders attach to artistic and cultural heritage. This is also demonstrated by the condition of major public institutions such as the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo, which is under constant threat of being shut down.

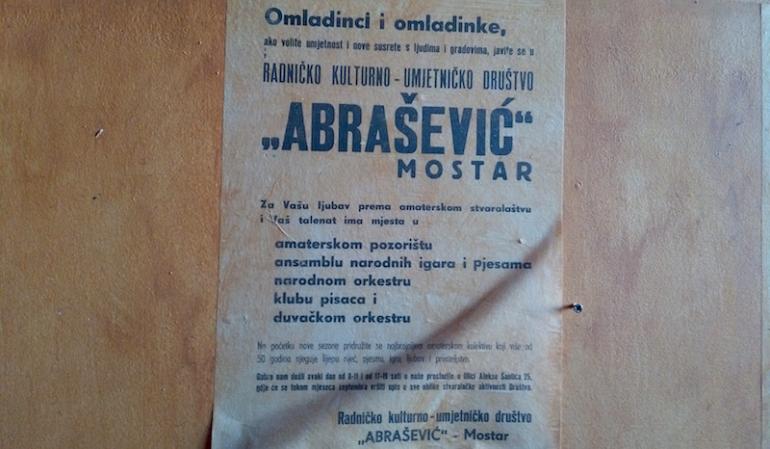

Abart, an initiative of the Abrašević Youth Cultural Center from 2009–13, took on the task of mapping Mostar’s hotspots of urban devastation and expressing their reactions to it through art. The Urban Imaginary virtual museum is the result of a project called (Re)Collecting Mostar, which draws on residents’ individual and collective memories as well as imaginary narratives and a new, artistic reading of the city’s history. These works are a reminder of the need to archive and collect, work that should be the duty of public institutions but here falls to individuals. For example, in Sarajevo, the organization Crvena (“Red”) has had to take over digitizing the archives of the Women’s Antifascist Front (AFŽ) due to public inaction. This saved the archival materials of a group that played a crucial role in women’s liberation in Yugoslavia while also pointing out the enduring need to liberate society as a whole. With institutions’ generalized disinterest in any type of liberation beyond the ethno-nationalist kind, such materials are, literally, in danger.

This is why I see these projects by artists and activists as the most important cultural events in post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina. The same goes for the few examples of cooperation between cultural institutions of the former Yugoslav republics, such as between the Mostar National Theatre and the Croatian National Theatre. The limited space of this article is not enough for me to recreate the context and mention some valuable initiatives to support my thesis, which is that the main battle for independent culture in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the fight for the right to remember. Under these circumstances, it is especially difficult to use art to promote the many important factors for liberating Bosnian society and including it in the artistic and political movements shaking up Europe and the world.

Of course, brilliant literary and musical works have come out over the last 25 years, excellent plays have been put on, and important films have been made, but without clear context, none of that makes for an integrated national culture. Culture is clinically dead in Bosnia and Herzegovina ; all of these initiatives are taking great pains just to keep it clinging to life. They are no less than critically important because, one day perhaps, the conditions may be right to fully resuscitate something that we may once again be able to call the culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina.